When I was twelve I saw something that changed my life. A YouTube video filmed in the cafeteria of a North Shore Massachusetts middle school. Some tween boys doing their darndest to churn out “Sweet Child O’ Mine” to an audience of folded up tables, the circular ones with the seats attached. In my memory they are perfect. Chugging away on the bass guitar in fingerless gloves was my cousin Kyle. Because of this video, replayed dozens of times on my mom’s desktop, I wanted to play in a band too.

Kyle and I were close as cousins could be for two pre-teens separated by several hundred miles, with limited access to rudimentary early social internet channels. Runescape was our primary hangout when apart, and then the sweltering shed behind our grandparents’ house in the summers, where we scrawled our names in crayon. A year older and a good deal bolder than I ever was, Kyle was the pinnacle of cool to me. He played in a number of teen bands, sometimes bass, sometimes melodica, and sometimes I don’t even know what. I dutifully liked whatever Facebook page they banded beneath. I don’t think I ever actually saw him play in person.

We both did high school theater, and cultivated a sense of drama about everything. He could reduce me to tear-soaked laughter easier than anyone. Together we were loud, bombastic, and complete terrors at family reunions where we had stiff competition. I went to college in Boston and figured we’d probably spend a lot of time together and get closer. That didn’t really happen, through no fault of our own, I think. Going to college is a sea change for anyone. We remained in touch, saw each other on holidays, and kept up what inside jokes we remembered.

At some point he introduced me to one of my great loves, The Dear Hunter. A band so perfectly suited for the both of us: drama kids with ambitious emo ideals and an unquenchable thirst for theatrics. A band for people who heard The Black Parade and thought “this needs more bassoon.” The last time we saw each other was at a Dear Hunter show in Boston. I think it was at the Royale.

Don’t worry, he isn’t dead.

There was a falling-out between families. It didn’t have anything to do with me or him, but we stopped talking. That was five years ago.

Things got better. Our parents all wanted to make up. That side of the family was invited to my sister’s wedding. We hoped to reconnect before the big day, however, and luck was on our side. It turned out, Kyle was spending the summer out in the Midwest not far from me. The two of us planned to get dinner, catch up.

It couldn’t have gone better. We were still ourselves. We still loved each other.

Kyle was driving me home after dinner, listening to MUNA, a band I would not have guessed he’d be into, when he said, “Wait. We gotta listen to Gator Rock.”

And he pulled from his center console something I had never seen before.

“Mom can we have Crocodile Rock?”

“We have Crocodile Rock at home.”

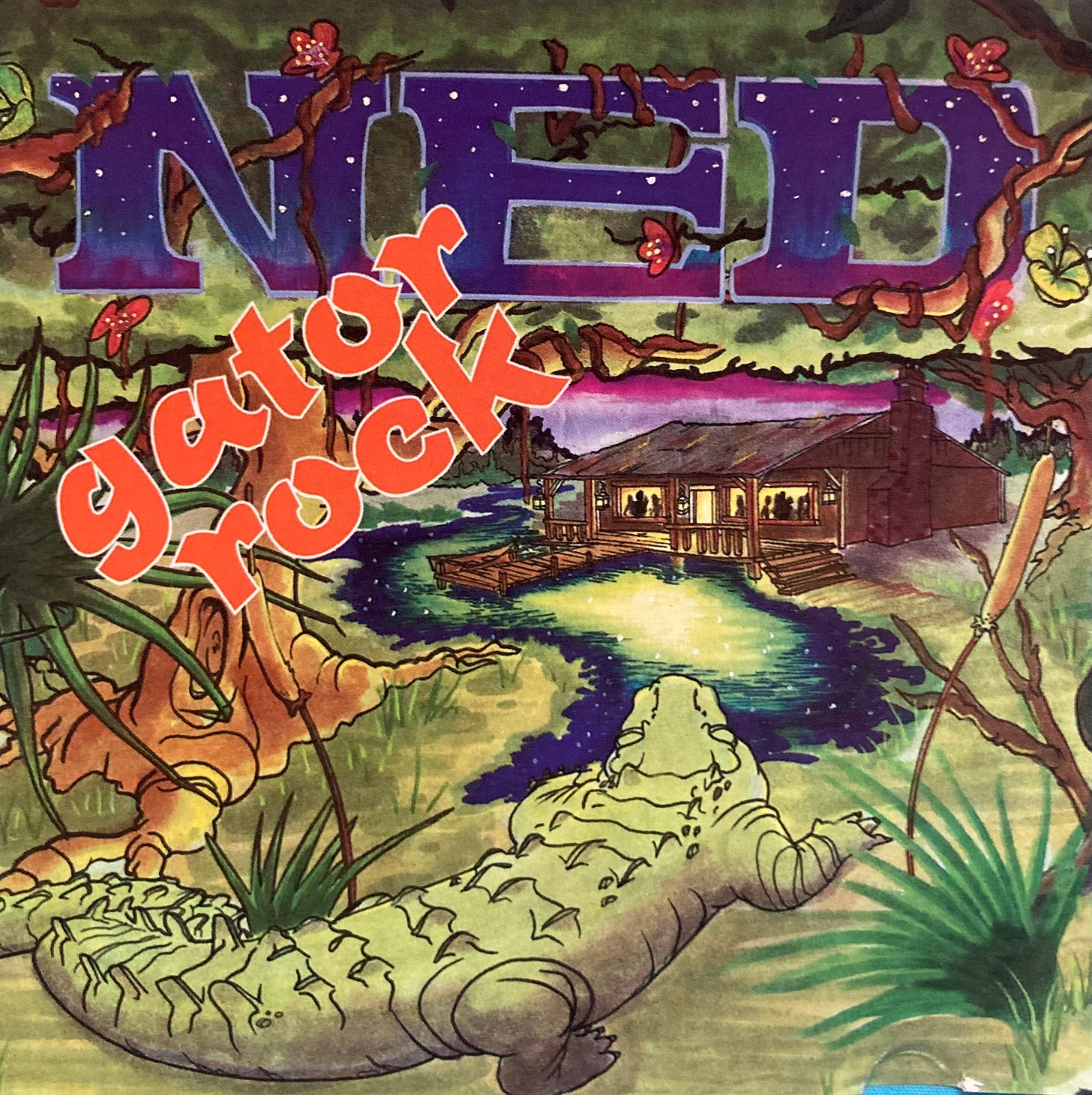

The Crocodile Rock at home:

This CD, he told me, had a long history.

Somewhere around the time we lost touch, he was working for a national park on a island, and he and his team were given a federal truck to get around. In that truck there was no aux, no radio signal, only Ned Albright’s self-published 1999 CD Gator Rock. Every morning at 4 am they would get up for work, and tool around, blasting this scaly symphony. After two months, the job was over and the federal truck returned. They left the CD where they found it, for whatever poor souls came next.

Then where did this copy come from? When Kyle got home he scoured the internet for something, anything about Ned, but came up with nothing. He found one copy of Gator Rock for sale on eBay for $100. The easiest purchase of his life. He burned copies for all his friends. I demanded my own.

Now, I’ve done some sleuthing myself, and few answers have revealed themselves. When I asked Kyle what ever happened to Ned, he assumed Ned was dead. What end could we imagine for this larger than life figure? Gone out in a Margaritaville blaze of glory, jumping his jet ski over the pier at his grown daughter’s birthday luau. Sailing into the Bermuda triangle with his dog and a harmonica, never to be seen again. Or, obviously, while golfing near the Everglades, gulped by gators.

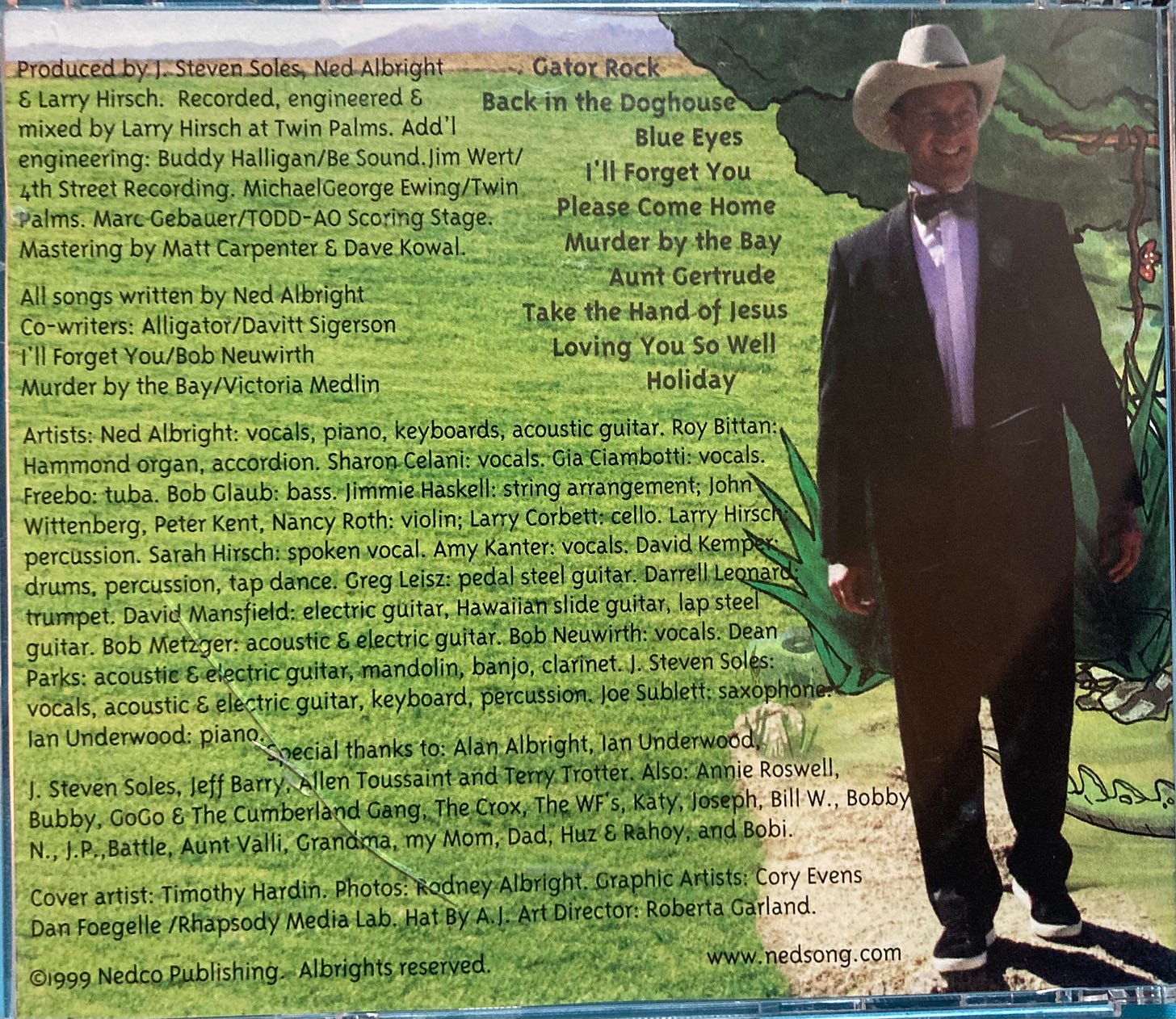

There is a Ned Albright who shares cowriting credits on two songs for The Monkees, “Acapulco Sun” and “All Alone in the Dark”. He was barely 20 when he wrote those songs. He also led a band called Tidbits on their, I think, singular record, Greetings From Jamaica, which I was unable to find on streaming but absolutely found on vinyl for $4.95 with $6 shipping. I haven’t gotten it yet but when I do I’m sure it’ll occupy me for weeks. Supposedly he’s been writing songs and earning credits since the 60s according to this AllMusic page. His personal website “nedsnotdead.com” 404s. The site listed on the back of Gator Rock “nedsong.com” similarly dead ends. I can’t confirm whether or not this is our boy though since his voice is absent from the Monkees’ recordings. However, J. Steven Soles, who is also credited with those Monkees collaborations, and for a time was a member of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, is listed on the back of Gator Rock, so chances are good. Bob Neuwirth, another Dylan associate, is also named in the liner notes.

Ned, if you’re out there, please tell us the truth.

Well. I found Ned’s spotify, and Gator Rock is there, under a eponymous title and with some disappointing new cover art. The page also says its from 2022 which simply cannot be true. I suspect Ned or his estate simply uploaded it then. The other songs featured on Ned’s spotify are some Garageband loops he’s laid some lackadaisical vocals over which I’m certain are some deep-quarantine coping mechanisms. And while the ability to stream these songs robs some of the mystique from that $100 CD, I am overjoyed to share Gator Rock with you all. Take a listen, I implore you.

This sounds like the guy who sold ZooBooks in the early 2000s trying to hit. This is divorced dad bar band Tuesday night turn up. This is Tom Bombadil lounge lizard lyrics. This is mid-life crisis music. This is an able set of studio musicians backing the harried heartaches of one man I assume they never saw again.

God’s name is invoked in the very first verse. The backup singers are tireless with their Florida football cheerleader chants. The chickenscratch guitar hollers honky-tonk wah-wah all over. I cannot take any of it seriously. Yet this song has been stuck in my head since.

Ned plies his haggard Eagles homage for ten whole songs. They’re worth a listen if only for the oddly cogent if entirely accidental concept album they create, from that Broadway opening to the hard knock lows of what I can only assume was an acrimonious divorce. The ballads may be cheesy enough to make the Cheesasaurus Rex queesy, and the child’s voice interjecting on “I’ll Forget You” raises some disturbing questions I’m sure Ned did not intend, but I love this record nonetheless.

(skip to 1:36 of this one for a bonkers plot twist.)

It is easy to dunk on music that doesn’t do it for us. I am more than guilty of hurling haymakers in these essays allegedly all about veneration and reclamation—intent on absolving the guilty from these pleasures. I spent a lot of words defending Brian Fallon’s much maligned agoraphobic divorce record, ending with the assertion that it’s hardly admirable behavior to laugh at another’s attempt to process pain through art. And so I commend Ned for making music, even if there wasn’t a great big crowd ready and willing to listen. If God made us this way, as “Gator Rock” insists he did, then he made us with an insatiable urge to create. Lying in wait inside a government truck on an island off the coast of Georgia, that CD found it's perfect audience. For the rest of my life I’ll be checking every secondhand shop for my own copy of Gator Rock.

I went looking for that YouTube video of Kyle and his band, but as you can imagine, sifting through several million covers of “Sweet Child O’ Mine” is an impossible task. I suspect Kyle is grateful for this failure.

Kyle always took music more seriously than me. His taste was always more esoteric, with an ear to technical and arcane composition. Yet Ned Albright Gator Rocked his world, and in turn, mine.

We got back to my apartment, and I said hold on, I have something for you. A few years ago I made some posters for The Dear Hunter’s album Hymns with the Devil in Confessional. I still had one for him.

Well, since I had a long drive back east for my sister’s wedding, Kyle said I should take Ned with me, and handed me his holy relic.

He’d see me there.

As per tradition, a picture of my cat:

Love you.

This is a delight.